I first met Ronnie Landfield in New York

before his debut at David Whitney’s new gallery on Park

Avenue South. That must have been 1968 or 1969.

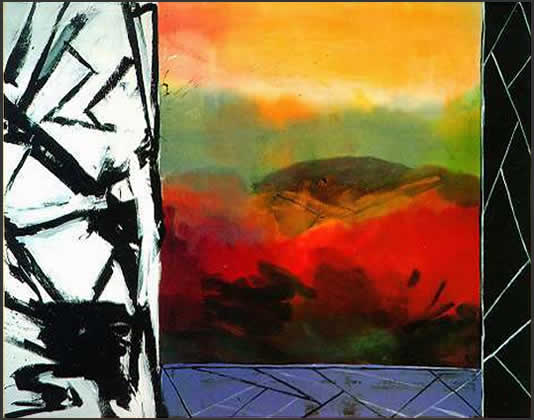

As is often the case with substantive artists, Landfield’s

area of interest — one of abstraction with a landscape orientation — was

already squarely set in its course. That course clearly carries

through twenty years to this day.

Although it is not my intention in this statement to engage in

critical analysis of Landfield’s art or trace its development,

I do have a thought that hopefully will benefit the visitor to

his upcoming exhibition at the Linda Farris Gallery in Seattle.

Ronnie Landfield paints abstracted landscapes. Landscapes that

are not motifs painted directly from nature but are rather invented

to meet his needs as an artist. His paintings are part of a tradition

of invented landscapes that goes back to the 15th century in Italy.

The Albertian invention of perspective led artists to invent deep

space landscapes such as the related versions of “The Agony

in the Garden” by Giovanni Bellini and Andrea Mantegna which

we encounter when we visit The National Gallery in London.

Leonardo’s fantastic landscape backgrounds and Giorgione’s

mystic vistas are the highlight of this tradition at the turn of

the century.

There is a special infusion of energy into tradition from the

north through Durer in the early part of the 16th century, and

again through Adam Elshimer a hundred years later. By the 17th

century this genre was in full swing both south and north of the

Alps, with the likes of Domenichino, Claude Larrain, Poussin, Seghers,

Rembrandt and Ruisdael, to name only a few.

By the 19th century the great English painters, Constable and

Turner, the Germans, Friedrich and Dahl and the French, from Corot

to Courbet, made their contribution. As do the great Americans,

Inness and Ryder and the much underrated Italian, Macchiaioli.

Through the end of the century and the beginning of the next we

have Van Gogh, Hodler, Cezanne and Mondrian, followed by Braque,

Matisse, Vuillard, Bonnard and Nolde. On this side of the Atlantic

we had Hartley, Dove, O’Keeffe and Avery painting in this

tradition.

The list is long — and I have left out many great artists.

However my inclusions should impress upon the reader that all the

artists mentioned above have tapped a deep psychological wellspring

with their landscapes. Regardless of their time and the movements

to which they have been assigned by the art writers, and regardless

of their personal styles or the theories that had been purported

to dictate their painting, each and every one strikes this psychological

chord that is so basic, that I suggest its origin is locatable

in the very creation and development of the eye. Which, after all

accounts, seems to have taken place in the landscape, on this planet,

over the last eight to ten million years. Therefore, the fact that

our attraction to the landscape — and the rendering of that

landscape — exists on such a basic level should come as little

surprise.

What is a surprise to me is that the great preponderance of art

writing in modern times has disregarded the visual enterprise — both

the making and the viewing of art — as a psychological one.

Rather the writers of art have, by and large, regarded the enterprise

to be a verbal one. Criticism offered by the philosophers of art

seem to act out some semantic need — a need to put art and

the entire framework for art in terms of language or some language

system.

This comes as a surprise to me because art seems to be clearly

visual, non-verbal and asemantic. The power of the visual is found

in the fact that great truths can be communicated without language,

or language systems, by and to individuals, without those individuals

needing language skills.

After all, the eye developed as an incredibly complex sensing

device over the last ten million years — long before the

invention of language.

What does all this have to do with an artist such as Ronnie Landfield?

Briefly, let us see.

Landfield arrived on the scene in the heyday of post painterly

abstraction. Greenbergian criticism, which held sway at that time,

seems to be based on the belief that art is self informed. Painting’s

physical aspects as an object, its shape and support, combine with

its formal aspects, its flatness and color, to form both the art

and the subject of the art.

For Landfield, and other artists whose work was judged by this

criteria, this often meant a more or less flawed reading when psychological

insights would have been more appropriate considering the origins

of his painting.

By the 1970s we had the rehabilitation of Marcel Duchamp, conceptual

and process art, and the much heralded death of painting. The emergence

of the great semiotic critics Michael Fried and Rosalind Krauss

ushered in an era where language signified the triumph of the idea

over the eye.

This was hardly the milieu to engage the serious painter in a

critical dialogue as the critics of the 1970s failed to do.

Landfield and the other serious painters (and there are at least

two dozen or more) who prevailed through the wall of indifference

and neglect of the 1970s faired little better in the 1980s, when

fashion and fashion marketing techniques became partners with the

Neo Marxist social thinkers such as Baudrillard. For some, mainly

the adherents to the Neo-Geo, this combination forged a belief

system where it is hard to separate the jargon of the social thinkers

from a marketing pitch that claimed that creativity in the arts

is a myth and that art is no more than a commodity object that

is traded — thereby reallocating capital in the postindustrial

world. These people claim that the artist no longer exists as a

thinkable possibility — therefore implying that the viewer

no longer exists. In short they are saying that art is not a visual

enterprise, but rather an ingredient in a model of capitalism.

Again we have an unhappy climate for the serious painter.

Where does this put Ronnie Landfield as a substantive artist in

1988?

Happily, I believe, he and other painters like him are not in

bad shape. These artists who have been steadily working over the

last two decades continue to paint. They make art as part of a

visual enterprise, an enterprise involving the artist, his intentions

and the receptive viewer.

The power of his art is that his intentions are accessible to

the viewer through the eye as a sensing device rather than through

any restrictive arbitration by a language system. The viewer is

then part of this visual-psychological enterprise, which is basically

asemantic.

A fact that the visitor to the Ronnie Landfield exhibition will

do well to keep in mind as they enter the gallery.

Nicholas Wilder

New York City

March 1988

|